So you want to raise a shape rotator?

It's time to learn about the Montessori puzzle progression.

Montessori puzzles show the genius of the approach in a clear way, by layering on different isolated challenges one by one. This post will cover the range of puzzles for babies and toddlers and how they progress in difficulty.

If you’re reading this and you’re a parent, know that I certainly don’t think you need to have the full collection at home. Still, it can be useful to understand why all these little details matter to Montessori educators.

The first one

As mentioned in a previous post, the first puzzle we offer babies, around 8-9 months of age, is the single, large circle. It looks like this:

This is introduced when they are already starting to use a tripod grasp (pointer, middle finger and thumb) and it focuses on one skill: aligning the circle shape with the circle-shaped hole. The previous skill of using these three fingers to grasp objects has already been developed with other materials, like the egg and cup, and is also present in other materials like the second object permanence box which is presented around the same time as this puzzle.

In my last post I gave a simplified explanation of how the progression went from this first puzzle onward, but in order to understand this more deeply, we can consider two main, parallel “tracks” starting here. The first we’ll look at is size:

Size

In order to prepare this size-discrimination skill, we now present a smaller single circle puzzle:

Because this is a smaller shape, there is less “circle slot” area and the child needs to be more precise in order to fit the circle.

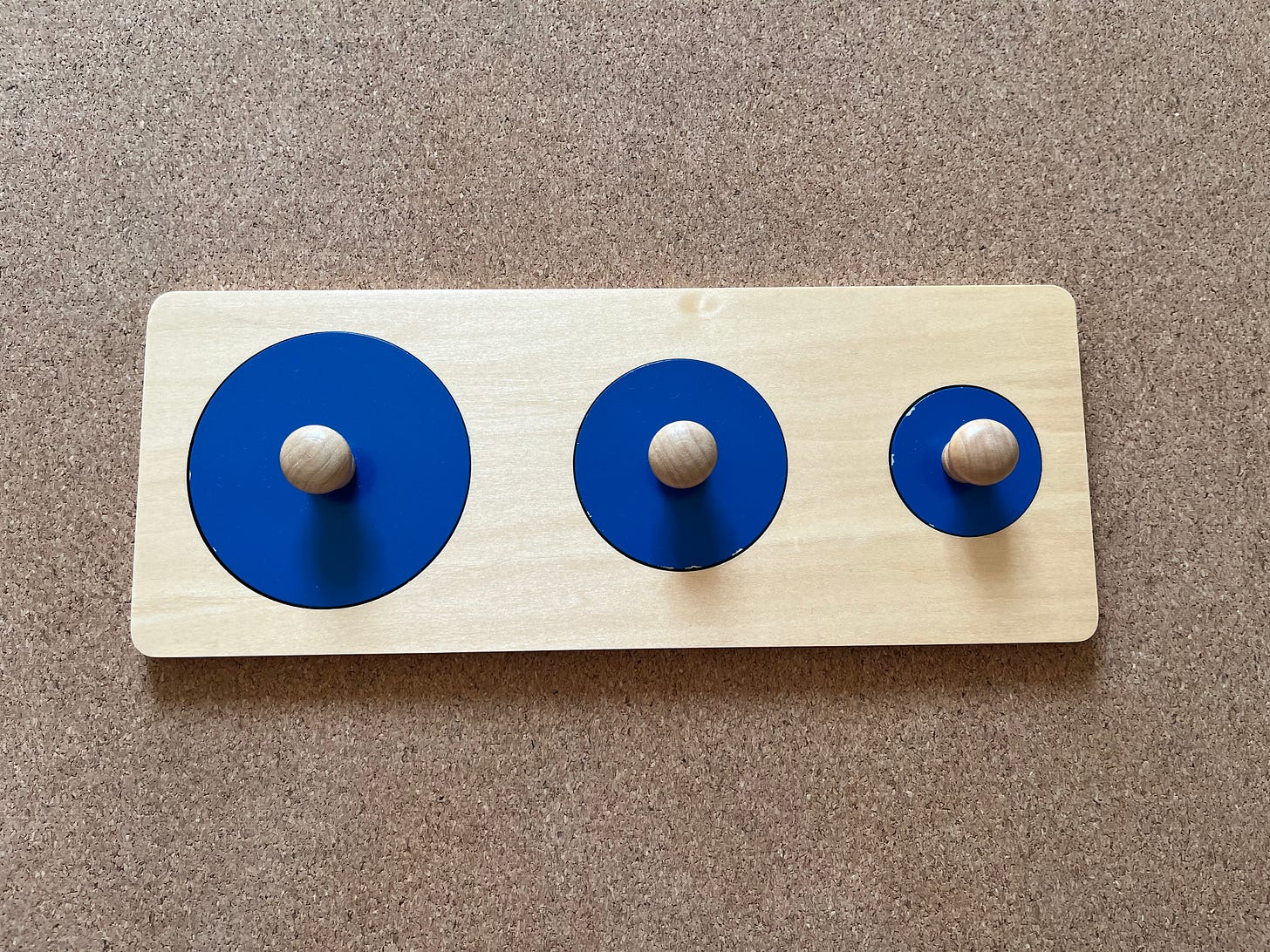

Once that is mastered, we can move on to the 3-circle puzzle. It looks like this:

You probably get the idea by now: the fine motor difficulty has been overcome, but there is a cognitive challenge in figuring out the size difference between these very similar-looking pieces.

Toddlers famously have trouble understanding that things behave differently when they are different sizes - it’s called the Scale error. If you didn’t know about this, I recommend watching this clip:

If you’re astute and noticed that the researcher prompted the first child to pretend, you can also read this paper, which explains there is basically no difference with/without prompting.

At this point, the child can discriminate between sizes and has started working with single irregular shapes (see next track), so we can introduce a puzzle with several irregular pieces that only vary in scale (usually between 3 and 5 pieces), like this:

It’s a big cognitive challenge, as the child has to figure out the correct rotation to use and which similar yet differently-sized piece fits into each hole. As you can probably see in this and the first track, as the puzzles advance and are made for older children, the knobs also become smaller, requiring a finer grip. This is also scaffolded in parallel through the use of other materials, such as the pincer block and various practical life and craft materials.

Shape

In parallel, there is the other “track”: shape. As you will remember, the first puzzle we offered the baby was the single circle. The thing with a circle is that it will fit within the hole no matter how you rotate it - it has infinite rotational symmetry. That’s why - once the baby has mastered this - we sequentially introduce two other single regular shape puzzles: the square, and then the equilateral triangle. They look like this:

At first glance it might look like it doesn’t matter which one you present first. However, the key difference between these shapes is in their rotational symmetry. A square has 4-fold rotational symmetry, meaning it can be rotated to fit in its hole in 4 different orientations (every 90 degrees). The equilateral triangle has 3-fold rotational symmetry, so it only fits in 3 different orientations (every 120 degrees).

This means the square is actually easier for babies to place correctly since they only ever have to rotate the shape 45 degrees at most, while with the triangle it’s 60 degrees. Wrist rotation is difficult for babies, so this small difference matters!

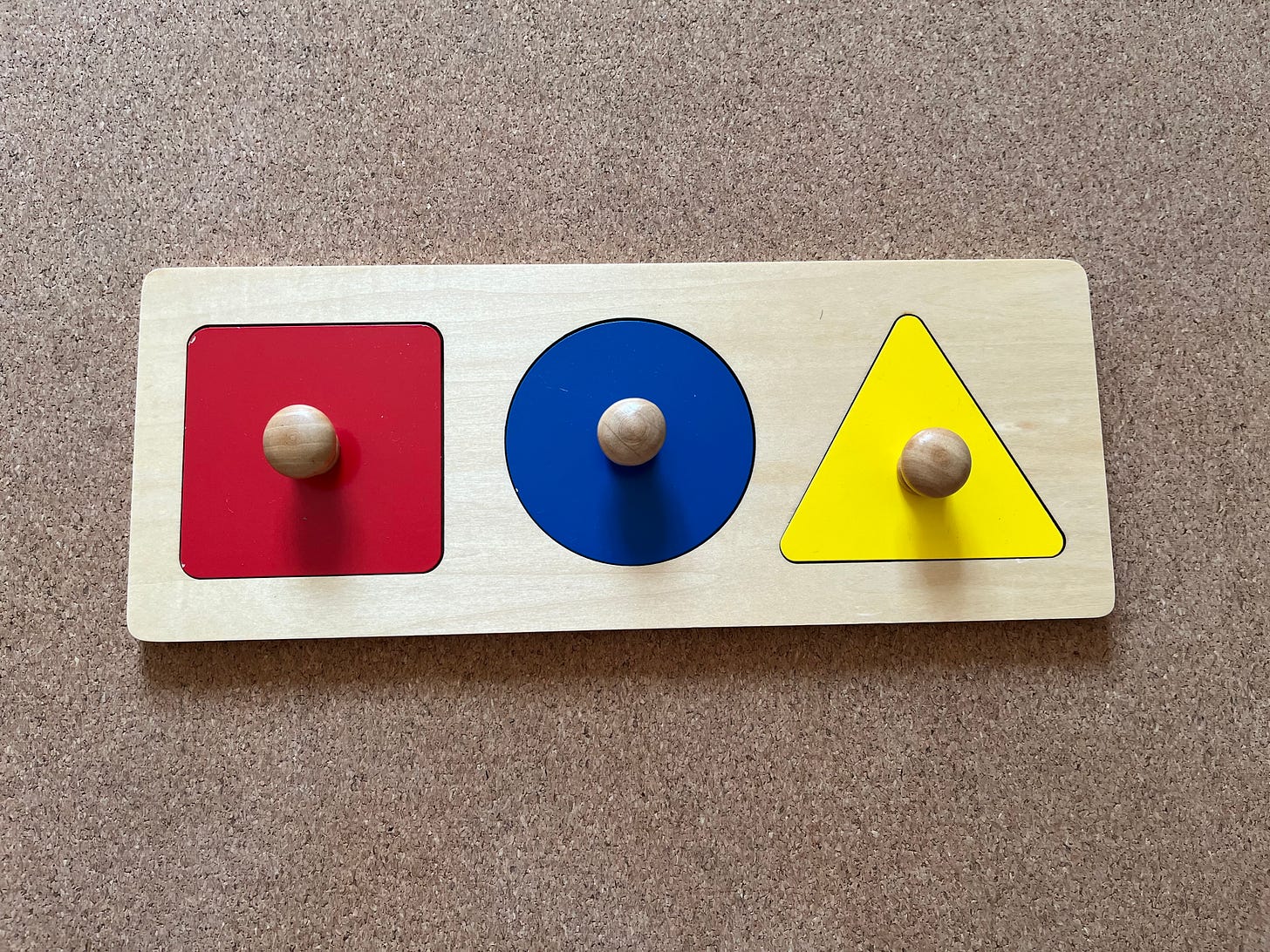

Once the baby is consistently using the triangle puzzle correctly, we move on to the next step: discriminating between the different shapes, when they’re all presented together. This is no longer much of a fine-motor challenge, but it’s a new cognitive challenge. It’s the regular 3-shape puzzle, and it looks like this:

You can’t put the puzzle together unless all of the shapes are in their correct spots. This makes the material self-correcting, as the child can tell whether he/she is doing the work correctly simply by interacting with the material, without any need for outside help. In Montessori we call this “control of error” - having a built-in-ness that is pedagogical in itself, sort of like interacting with a computer game that won’t let you move forward and signals if there is something wrong with your input through audio or visuals.

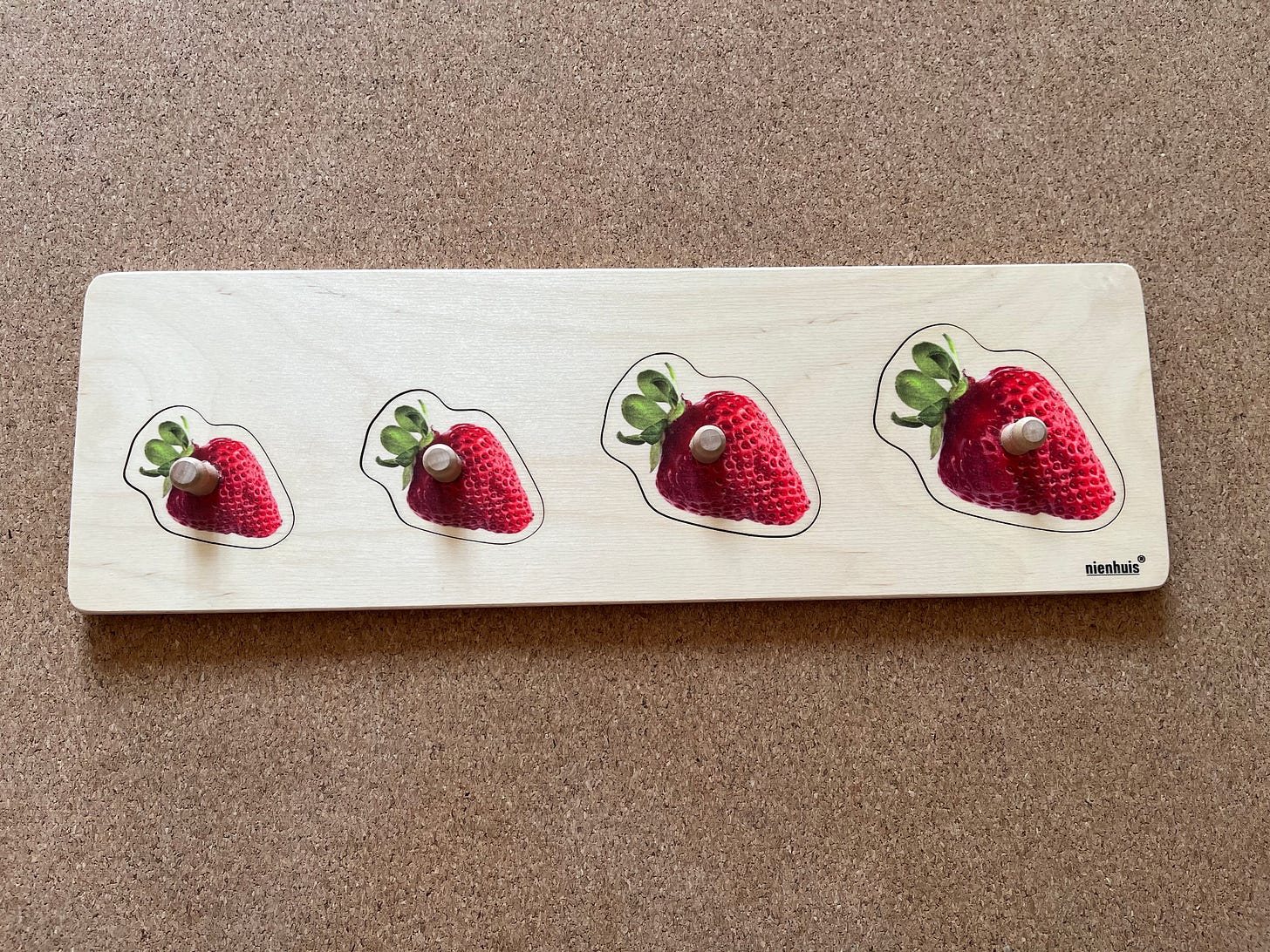

Now that the child can discriminate between shapes and has the motor skills necessary to rotate them into their correct orientation, it’s time for a new challenge: an irregular single-shape puzzle. These can be of animals, plants, vehicles or other things that a child sees in their day-to-day life. They look like this:

This is tricky, because unlike the circle, the equilateral triangle or the square, this organic-shaped piece will only fit in one orientation. The child has to be much more precise in order to make it work. It’s usually a big piece, to make it easier to place.

After a child is able to do these easily, we can introduce irregular multiple-piece puzzles of different shapes. They can be very different (slightly easier) or very similar (slightly harder). They usually have 3-5 shapes. Now the child has to look at the different, irregular slots, figure out which piece goes where, and fit it.

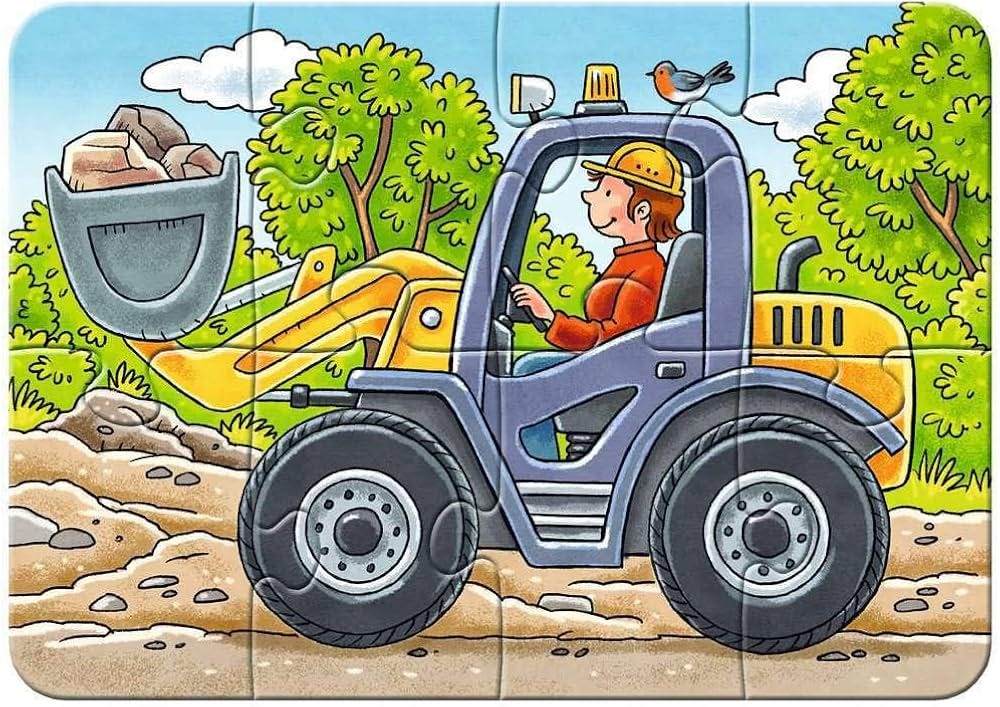

The next challenge is a “parts of a whole” multi-piece puzzle, which looks something like this:

Here, the toddler needs to put together several differently-shaped pieces, which usually contain a relevant “part” of something (like a goat’s legs, head, body), and organize them into a full picture of something (like a goat!). The frame helps because it provides clues in the form of negative space, but it can be very hard to figure out at first which one goes where, and it can take many tries.

Jigsaw puzzles

Now we can bring in conventional jigsaw puzzles: ones that are assembled through locking mechanisms that have to fit precisely within each other. We start with very simple 2-piece or 3-piece puzzles, and offer one at a time. Ideally they are contoured (instead of square or rectangular) so that there is an extra clue as to the correct configuration of the pieces.

As the child figures out how they work, we start offering puzzles with more pieces to add complexity. It’s much more helpful for the child if the jigsaw pieces only fit in one particular way - that way they have a control of error for their work. This is another characteristic of Montessori materials that I’ll explore in a future post.

The next step is to present a traditional jigsaw puzzle that comes together as a rectangular image. For this, we can use a tray that is approximately the size of the puzzle, at first, to help give them a sense of the scale of the finished work.

As you’ve probably memorized by now, start with fewer pieces, and gradually increase the complexity as they master those first levels. Puzzles like these tend to come in “my first puzzles” (or similar) sets in progressing levels.

Puzzles ftw!

There are also other interesting variations such as block puzzles, with require 3D rotation, puzzles with components that screw together, and many other options out there. I would encourage you to look for simplicity whenever possible, and observe your child so you can offer them something at the right level of challenge.

Puzzles are engaging for humans of all ages, and they are really good educational materials for babies and toddlers. In Montessori primary and elementary classrooms, they are used as biology and geography materials.

Puzzles help kids develop:

Fine motor skills

Hand-eye coordination

Finger grip: tripod / radial digital grasp → inferior pincer grasp → refined pincer grasp (more on this here)

Wrist rotation

Precise hand movements

Cognitive skills

Shape discrimination

Size discrimination

Concentration

Spatial reasoning

Problem-solving

Planning

Memory

Frustration endurance

Social skills like collaboration, turn-taking - if working with others

Now consider the whole ecosystem of a Montessori classroom: there is only one of each puzzle for all the children in the room to use, so they must take turns, and each one has a specific place on a shelf that it should be returned to. Children have to carry it carefully to a table or a mat on the floor to work, either by themselves or with others.

There are other skills being built and needs being met: patience, grace and courtesy with others, order, balance and gross motor control. In a Montessori classroom, everything is purposeful and complimentary. There are many other “tracks” being worked on alongside these, and they both assist and are assisted by the development of these skills. But I’ve always found puzzles fascinating, and I hope now you do too.

If you found this post valuable, consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber:

Visit my website babieswithb.com to find out more about what I do.